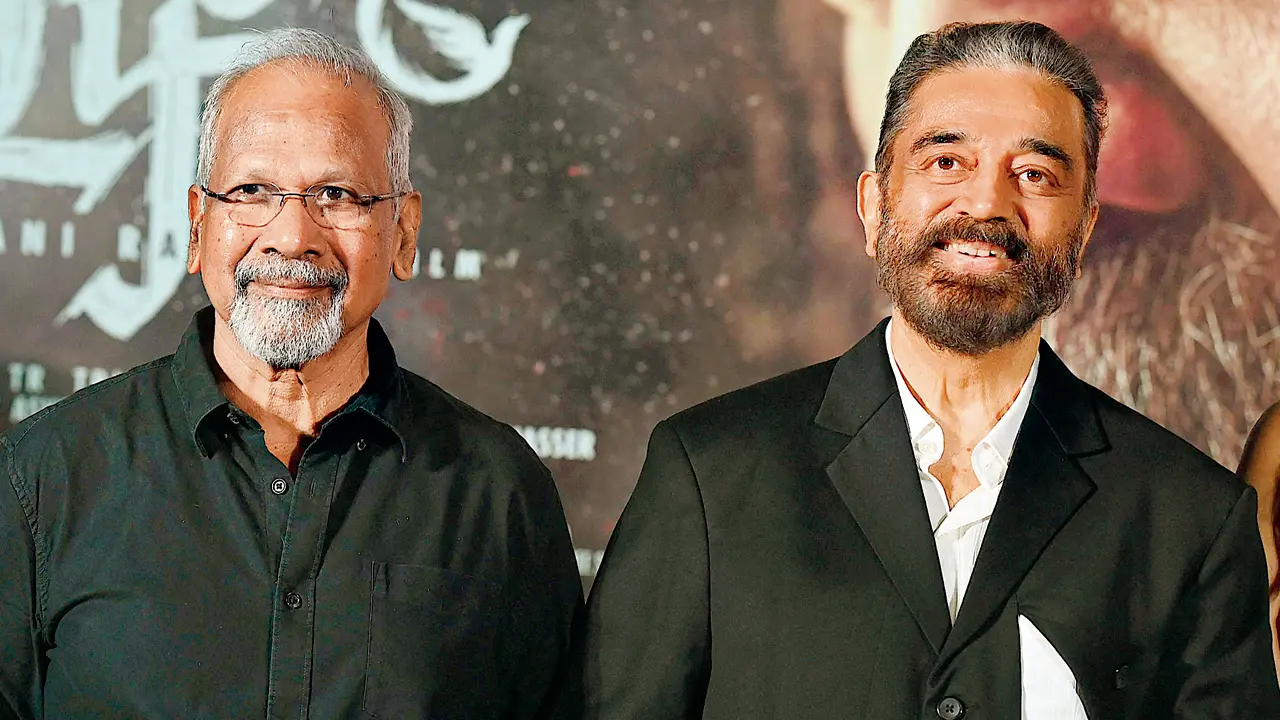

What took you more than 30 years to reunite with Mani Ratnam?’ This question has made a frequent appearance since Kamal Haasan kicked off the promotions for his next, Thug Life. When we express our curiosity, the superstar smiles before saying, “I’m almost tempted to request all of you not to ask that question because I can only say sorry, it’s our fault. We should have done it earlier.”

In 1987, the two gave Indian cinema the much-loved Nayakan. Thirty-eight years later, as the actor reunites with one of his favourite filmmakers for the gangster action drama, he reveals that an encore was always on their mind. “Sometimes, we were thinking too big, and at other times, we would think something small and then [shoot it down] believing that these are the days of big films. Sometimes, I’d come up with an idea, and Mani would already be working on something else, and vice versa. But we were gently, subconsciously, and from a distance, inspiring each other,” grins the actor.

A still from Thug Life

That decades-long inspiration has resulted in Thug Life, which also stars Silambarasan TR, Trisha Krishnan, Abhirami, Ali Fazal, and Sanya Malhotra. How was it working together considering they both have come a long way from Nayakan? Haasan is an even bigger star today, and Ratnam, one of the greatest filmmakers in the country. Did the actor try to impress his director this time? “I can’t impress the director; the character can. He booked Kamal Haasan not because of the stardom. Left to us, I think we are both overpaid. But then if we let that go, they [the industry] won’t respect us. So, we will take our cut.”

This time around, their collaboration has also taken a different turn. Haasan not only leads the June 5 release, but has also co-written and co-produced it with Ratnam. And he firmly believes that nobody else could’ve done justice to the film as far as production is concerned.

Kamal Haasan’s second collaboration after their gem, Nayakan

The superstar states, “[We are the kind] who will put our money into the film. Suppose all that we have shot is destroyed, we won’t panic. We will go ahead, put our own money, and do it [again]. Another producer could not have taken the pressure of Thug Life. We made some difficult decisions.”

Production and direction were a natural graduation for the actor. It all stems from his endless love for movies and deep respect for the craft. His passion is evident as he says, “I never walk out of a film because that would [mean] insulting my peers. We’ve made stupid films. When I say that, I don’t include Mani’s films in it. But I have, because I needed finance for my own productions.”

That is a career lesson Haasan learnt from late actor and filmmaker Shashi Kapoor. “He would be singing a song on top of an elephant in Shaan [1980], and the same elephant would be beside him in Junoon [1978]. I had asked him, ‘Can I also [juggle mainstream and parallel cinema]?’ He said, ‘Sure. It’s pragmatism. Don’t mistake it for valour.’ Some of the great Italian directors did commercial films, made money out of them, and [used that] to make films that would live on.”

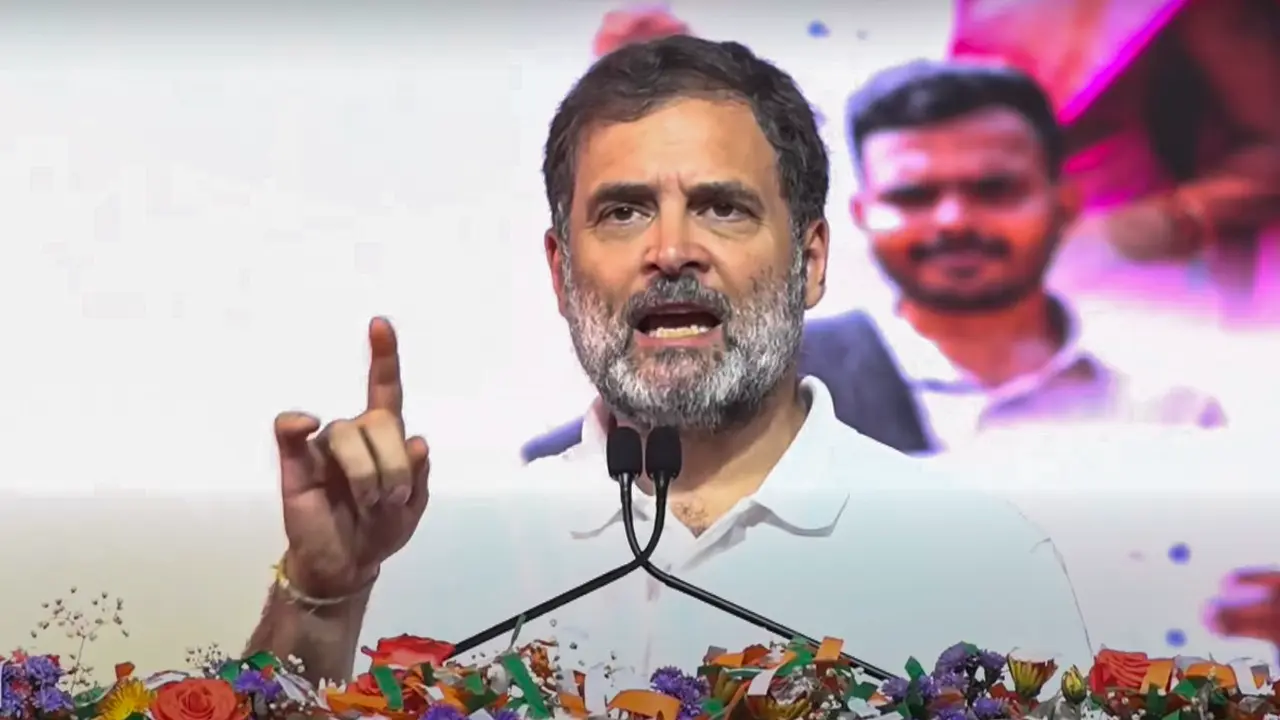

Kamal Haasan

Wise career lessons, unmatched talent, and a progressive worldview have come together to shape Haasan’s enviable filmography that spans over six decades and different branches of filmmaking. Through his films, he has positioned himself as an artiste who often mirrors society’s fractured reality. In Nayakan, he showed the perils of violence. But today, how does he view Indian storytelling’s penchant for violence and the audience’s love for it? He points to a chapter in history to make his case.

“You know, after the Second World War, America kept making musicals; they didn’t want any violence. Now we’ve had enough peace. Now, the time of violence has begun, and that’s reflecting on screen. Earlier, the angry young man was only angry; now he will become violent if his voice is not heard. At least, a soapbox oratory should be allowed in front of the Red Fort. Listening to [the common man’s] voice is what great leaders have always done. After Partition, look at the kind of films we made — Naya Daur [1957] and Waqt [1965]. Even now, cinema is reflecting society, and [the violent films imply] that society has become violent. If you want proof, watch any television channel.”

Leave a Reply